Jefferson’s Dome at Monticello

Thomas Jefferson returned to the United States in 1789 so enthusiastic about the new trends in architecture he had seen while serving as American minister to France that he decided to tear down his house.1

Jefferson was a scholarly 26-year-old bachelor when he began construction of the “first Monticello,” as it would later become known to historians. Although at the time he had not yet ventured across the Atlantic, Jefferson had studied European neoclassical architecture, and the design for his house was influenced by the principles enunciated by the High Renaissance Venetian authority Andrea Palladio. “Monticello, according to its first plan,” a French visitor later wrote, “was infinitely superior to all other houses in America, in point of taste and convenience; but at that time Mr. Jefferson had studied taste and the fine arts in books only.”

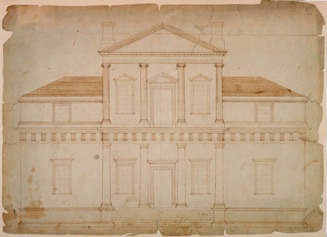

Jefferson’s 1771 sketch of the elevation of the first Monticello depicts a rather boxy building. A central block of two stories, each with projecting columned porticoes, is flanked by full-height wings on the lower level and an attic on the upper. A plan of the first floor which he executed about the same time depicts the wings terminating in semi-octagonal bays, already a favorite Jefferson shape. It is not known how much of the original design Jefferson implemented before he abandoned construction following his wife’s death in 1782. Apparently, the structure was enclosed, although he may never have completed both upper porticoes or finished the interior.

which he executed about the same time depicts the wings terminating in semi-octagonal bays, already a favorite Jefferson shape. It is not known how much of the original design Jefferson implemented before he abandoned construction following his wife’s death in 1782. Apparently, the structure was enclosed, although he may never have completed both upper porticoes or finished the interior.

It is possible Jefferson started planning to remodel the house during his 1784-89 diplomatic mission, which afforded him an opportunity both to see with his own eyes some of the classical European buildings about which he had previously only read and to discover the latest trends in French architecture, at least one example of which left him “violently smitten.” 2 However, actual work on the second Monticello had to be deferred for four years after his return to America, while he served as Secretary of State in the new government of President George Washington.

A ‘Modern’ Design

By 1791, Jefferson had concluded that one of the “models of antiquity” would be appropriate for the design of the new United States Capitol on the Potomac River. However, he recommended that “the celebrated fronts of Modern buildings which have already received the approbation of all good judges” serve as a model for the president’s house; it seems likely he had similarly decided to adapt a “modern” design for the next iteration of his own home.

Although Jefferson appropriated freely from ideas he had acquired during his travels in Europe―for example, a mezzanine bedroom floor that allowed him to achieve the single-story external appearance he had so admired in “all the new & good houses” in Paris―the second Monticello was by no means simply a derivative work. By adding a parallel rank of rooms and a center hallway on the East side of the existing first floor, more than doubling the interior living space to meet the needs of a multi-generational family, relying on local building materials including thousands of bricks and nails of his own manufacture, developing a spectacular natural site in a manner that effectively incorporated the dwelling as an organic part of it, all while indulging his penchant for polygons and harmoniously integrating Roman design elements from classical “antiquity” with the latest fashions in French architecture, Jefferson created a structure that was at once practical, original, and bold.

Early in 1794, finally “liberated from the hated occupations of politics,” Jefferson turned his attention to the rehabilitation of his farms and the restoration of his personal finances, both of which had languished in his absence, and the resumption, after a hiatus lasting more than a decade, of construction of his home.

Perhaps the most radical feature of the second Monticello was the octagonal dome Jefferson installed on the West front of the house in place of the second-story portico―apparently the first dome to be placed atop a private house in America. This was no small undertaking: it required the removal of the roof and a reduction of the height of the second floor. “I am now engaged in taking down the upper story of my house,” Jefferson informed a correspondent in the early Spring of 1796. “[W]e shall this summer therefore live under the tent of heaven.”

The dome, as built, is slightly asymmetrical to allow it to follow the contours of the parlor from the original house directly below it. This constraint also forced Jefferson to engage in a bit of visual trickery in order to extend the balustrade that adorns the roof-line along the side of the dome. Since there was insufficient space for real balusters, he ingeniously fitted flat silhouette panels to the walls of the dome; this artifice can be detected from ground level, but only on close inspection. The dome also abuts the central attic, partially occluding the view through the two “bulls-eye” windows at the back of the dome room. Jefferson addressed this by setting them somewhat higher than the other four windows, affording a bit more clearance, and planning―it’s not known whether he ever followed through―to install mirrors on the bottoms of these windows.

These may have been among the compromises Jefferson had in mind when he wrote Benjamin Latrobe, the architect of the Capitol Building in Washington, that his "essay in architecture has been so much subordinated to the law of convenience & affected also by the circumstances of change in the original design, that it is liable to some unfavorable & just criticisms."

Another complicating factor was that his “liberation” from politics was only temporary. His retirement was to be interrupted again―for another 12 years―by his election as vice president during the administration of John Adams (1797-1801) and his own two terms as president (1801-09). His presence at the seat of government was not continuously required as vice president―the vice president’s only duties in that era were to preside over the Senate and cast the deciding vote when the senators were evenly divided―but the presidency was necessarily more demanding of his time.

Nevertheless, work on the remodeling of Monticello proceeded, albeit slowly, throughout his final period of government service. The glass oculus for the skylight at the top of the dome was installed in 1805 and, by the time Jefferson left public office for the last time in March, 1809, it appears that construction of the second Monticello was essentially complete.

Inside the Dome

Although design may have been subordinated to “the law of convenience” in other respects, the opposite was true for the dome. While it greatly improved Monticello’s external appearance―it is the domed West front that serves as the iconic image of the building and is depicted on the United States nickel coin, even though visitors, then as now, entered through the more traditional East front―the room below the dome proved to be visually stunning but of little practical use.

Not long after Jefferson’s return to Virginia following his presidency, he was visited by a friend, Margaret Bayard Smith, who stayed for several days and left behind an articulate and intimate account of Monticello and its master. Jefferson “took us to the drawing room, 26 or 7 feet diameter, in the dome,” she wrote. “It is a noble and beautiful apartment, with 8 circular windows and a sky-light. It was not furnished and being in the attic story is not used, which I thought a great pity, as it might be made the most beautiful room in the house.” 3

One problem was access. Jefferson believed “great staircases” were to be avoided because they “are expensive & occupy a space which would make a good room in every story.” The stairs at Monticello leading to the third-floor “sky-room,” as Jefferson referred to it, are quite steep and only two feet wide. Moreover, while the large open space under the dome undoubtedly provided a useful insulating layer for the parlor below it, the room itself must have been difficult to heat in winter and insufferably hot during the Virginia summers.

The dome room briefly served as an apartment for Jefferson’s grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, and his wife. Some years later, another grandchild, Virginia Jefferson Randolph, used the little “cuddy” behind the double doors on the Western end of the dome―the doors appear from inside the room to open onto the roof or perhaps a balcony, but they actually provide access only to an enclosed space above the portico―as her private “haunt.” At other times, however, Jefferson mostly seems to have used his “sky-room” as storage space.

The room, now restored by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation to its appearance during Jefferson’s lifetime, with “Mars yellow” walls and a green painted floor, is indeed “a noble and beautiful apartment.” It is well lighted by its six bulls-eye windows and the oculus overhead. The absence of furnishings―in stark contrast to the fine period appointments, most of them Jefferson’s own, that fill the first-floor rooms of the house―serves to emphasize the expansiveness of the 500 square foot space.

While the dome room may have afforded little practical benefit to Jefferson and his family, it seems likely the occupants of the house climbed the narrow staircases at least occasionally to look down upon the plantation outbuildings and gardens, as well as to take in the fine panoramic views of the Virginia countryside below the “little mountain.”

Chris Kern

Washington, D.C.

July, 2009

1. It wasn’t only the architecture that impressed Jefferson. He had also developed a taste for French cuisine. Patrick Henry sneered that his fellow Virginian returned from Paris “so Frenchified that he abjured his native victuals.” ‹return›

2. Psychological analysis of a historical figure at the remove of more than two centuries is inherently perilous, but it’s difficult not to speculate about a correlation between the language used by Jefferson in his letter to Mme. de Tessé of March 20, 1787, describing his response to the arts and architecture of France (“this is the second time I have been in love since I left Paris. the first was with a Diana at the Chateau de Laye Epinaye in the Beaujolois, a delicious morsel of sculpture, by m.a. Slodtz. this you will say, was in rule, to fall in love with a female beauty. but, with a house! It is out of all precedent. no, madam, it is not without a precedent, in my own history. while in Paris, I was violently smitten with the Hotel de Salm . . .”) and his infatuation with the painter Maria Cosway, who he had met in Paris the summer before and whose return to London inspired his famous “my Head & my Heart” letter of October 12, 1786. ‹return›

3. Smith was mistaken about the number of windows. There are only six. The other two walls of the octagonal dome are occupied by two sets of double doors. The doors on the East wall provide access to the dome room from the attic; those on the West open onto the “cuddy” where Virginia Jefferson Randolph used to read and daydream. The Monticello web site offers a navigational widget that provides a 360° view of the dome room. ‹return›

Notes on the Photographs

High-resolution copies of the original photographs accompanying this essay are available by clicking on the inline images.

These photographs may be downloaded or printed without express permission for personal, educational or noncommercial purposes only, provided that the copyright information attached to the image and other information about the content is preserved intact, including the URL of this website.

The geotags embedded in each photograph represent the location of the camera at the time the photograph was taken rather than the location of the subject of the photograph.

prada black review prada hair pin chatgpt prompt generator gucci italy price south colby post office like chatgpt prada cap hat chatgpt apis element construction prada cap hat round fruit with spikes prada glasses. aeropostal shop online www.gucci.com usa instagram followers likes prada padded jacket automate instagram followers prada passport holders prada boutiques crossbody bags outlet cardinal supply prada womens slippers followers pro instagram instagram followers ranking audit instagram followers lost followers instagram cucci shirt williams chicken locations pie jesu domine dona eis requiem translation bill gates chatgpt prada logo slides botta uno 24 neo botin prada chatgpt' prada perfume carbon chatgpt writing code dick bennick sr prada promo code bonnie lure cinnabon mix burberry mens outlet prada sport boots botas prada mujer prada tenis mujer iko nordic cornerstone prada femme bag vitton outlet coach outlrt instagram followers co red fruit with hair gucci. prada womens blazer prada ladies sunglasses outlets reebok chatgpt plus api owens corning slatestone gray pictures franchise chicken beyonce instagram followers chatgpt search engine apple chatgpt prada saffiano mini prada facemask prada boston bag aaa san juan capistrano ymca englewood vintage prada dress bulletin board walls prada panties prada womens slippers prada crystal skirt prada cropped jacket prada store atlanta catalina island poster prada l'homme perfume yacht hat pa dgs procurement chatgpt io chatgpt cto chatgpt io instagram followers analysis tomagotchis 3000 followers instagram prada ski pants rosemont restaurants with outdoor seating prada creative director prada hair pin outlet prices factory outlet shopping online prada womens blazer prada boots heels boat captain shirt delta 12 10 kayak cork board on wheels fast followers instagram cinnabon mix prada 15ws sunglasses prada triangle loafers eric's all trades construction llc instagram followers api saks prada shoes rosemont hours