A Belated Correction: The Real

First Broadcast of the Voice of America

Responsible news organizations publicly acknowledge errors when they discover them.

Sometimes it takes a while to check the facts and set the record straight.

Every year on February 25, I and my former colleagues at the Voice of America commemorate our first broadcast. VOA went on the air during the initial bleak months of 1942 following the entry of the United States into the Second World War, when we and our allies were taking a beating on every battlefront. We use the anniversary to remind ourselves, and assure our international audience, that we are still guided by the introduction to that long-ago program, which was relayed by shortwave radio across the Atlantic Ocean and transmitted to Nazi Germany by the British Broadcasting Corporation: The news may be good or bad; we shall tell you the truth.

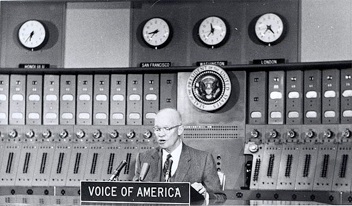

Some years, especially anniversaries with round numbers, VOA stages elaborate formal ceremonies. Other anniversaries are more modestly marked with a press release, a memo to the staff, and perhaps a small reception. On February 25, 1957, we rated a presidential visit. The wartime general and postwar president, Dwight Eisenhower, began a formal speech on foreign policy that day from our Master Control room by saying: “For fifteen years now the Voice of America has been bringing to people everywhere the facts about world events, and about America’s policy in relation to these events.” VOA broadcast the speech worldwide.

Only problem is, we’ve been celebrating the wrong date.

The reason for the mix-up isn’t clear. The wartime leaders who were developing the country’s foreign information strategy were primarily concerned with the substance of what to say to the populations of Germany, Italy and Japan, and the countries the Axis powers had occupied; maybe none of them thought at the time that the first “Voice of America” radio broadcast was a significant enough event to merit the creation of a formal documentary artifact. Needless to say, they could hardly have been expected to guess they were launching a national institution that would survive well into the next century. Or perhaps—in a phenomenon that will be instantly recognizable to anyone who has ever worked in a government bureaucracy—the official date was . . . ahhh . . . adjusted ever so slightly in 1957 to accommodate the schedule of President Eisenhower so he could make a speech on VOA’s “anniversary.”1

However it happened, apparently nobody at VOA noticed when the American actor and film producer John Houseman, the first Voice of America director, recalled in his 1979 autobiography that the initial program had been broadcast on February 11, and even published a photograph of the dated script to prove it. It should have been obvious to anyone reading Houseman’s book that the February 25th anniversary we had been celebrating was incorrect.

Well, actually it turns out Houseman had the date wrong, too.

Roberts’ Remonstrance

I first learned there was a question about the anniversary from my old friend and former boss, Alan Heil, author of Voice of America: A History. Alan sent me a copy of a reminiscence by the diplomat and author Walter R. Roberts, apparently the last survivor of the Voice of America’s original staff, who noted the discrepancy between the date of the first broadcast celebrated by VOA and the one reported in Houseman’s autobiography—and disputed both of them. His recollection was that it was earlier than either of those dates and he concluded that it probably took place on February 1, 1942.

In the summer of 2010, shortly after I retired from “the Voice,” Alan introduced me to Walter over lunch. Alan and Walter, at 94 still articulate, animated and very much in command of his detailed memories of that time almost seventy years earlier when the United States began broadcasting to the world, persuaded me to have a go at finding definitive evidence of when the Voice of America first went on the air.

And so I signed up for a researcher’s credential at the U.S. National Archives and began working my way through the records of the government’s World War II information program. The search was complicated by VOA’s baroque organizational history. The first Voice of America program was broadcast under the aegis of the Coordinator of Information, a department that included both the collection of information—i.e., intelligence—and the transmission of propaganda (yes, that’s what they unabashedly called it) to both American and foreign populations.

Within a few months, the office was split up into two new agencies: the Office of Strategic Services, a predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Office of War Information, to which the Voice of America was transferred. After the war, international radio briefly became a responsibility of the Department of State until, in 1953, a new United States Information Agency was formed to manage all foreign information and exchange programs. (USIA was abolished in 1999, and a nine-member Broadcasting Board of Governors was established to provide oversight over U.S. international broadcasting.)

Each of the departments and agencies that were successors to the Coordinator of Information wound up acquiring some of its wartime files and each of them, during the intervening years, dutifully transferred them to the National Archives, which makes official records of the government available to historians, other researchers and the general public. But because the documents arrived at the Archives from so many different sources, it was probably inevitable that they would be catalogued inconsistently. And since one of the tenets of the archival process is that records must be preserved precisely as they are received, the surviving documents are organized according to the idiosyncratic filing systems of each transmitting agency—in most instances, inside the original file folders that were delivered to the Archives.

The Paper Chase

During August and early September, 2010, I made several visits to the Archives’ cavernous facility in College Park, Maryland, to search for the 68-year-old files of the Coordinator of Information. I also queried the Franklin D. Roosevelt presidential library in Hyde Park, New York, in the hope that the coordinator, the colorful New York lawyer William J. (“Wild Bill”) Donovan, or one of his principal subordinates, had sent President Roosevelt a memorandum announcing that the radio broadcasts to Germany had begun. (No such luck.) I looked at hundreds of documents dating from the middle of 1941 to the end of the war in 1945, but only a few were from that critical period in January and February, 1942, when the Voice of America first went on the air. Most of the latter referred to information programs other than international radio and the few that did mention broadcasts to Germany provided no clear evidence of their starting date.

Finally, after a series of dead ends, I stumbled on a catalog entry that referred to “scripts of news broadcasts to various countries overseas . . . [summarizing] events of World War II for radio listeners” that had been transferred to the Archives by the U.S. State Department after the war. Unfortunately, the records were nearly lost in archival limbo. No physical location for them within the vast College Park complex had been recorded in the standard “finding aid,” rendering them effectively inaccessible. A young Archives technician performed some complex detective work involving a location index that had long since been retired (apparently the National Archives maintains archives of its obsolete archival indexes!), and triumphantly produced an entry for the Domestic Branch of the Office of War Information—the outfit that produced morale-building propaganda for the American public. I explained that the Domestic Branch couldn’t have created the materials I was looking for, but she persuaded me to have the records “pulled” anyway, and a couple of hours later I found myself thumbing through boxes of radio scripts in several languages from the first months of 1942: somewhat faded, awkwardly folded, occasionally torn, but still quite legible documents, the oldest of the surviving copies printed on fragile onionskin translucent paper.

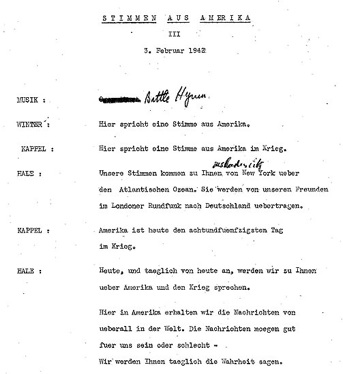

The earliest script preserved in the file was the one for Tuesday, February 3, 1942,2 but it is clear that wasn’t the first Voice of America program because at one point the script calls on one of the announcers to refer to something he said “yesterday.” The reference to the previous day’s program obviously means there had been a broadcast on Monday, February 2. But was that the first? Walter Roberts and I had independently noticed that the illustration of the February 11 script in the Houseman book had a Roman numeral XI typed under the title, and guessed that it might mean it was the eleventh in the series. Sure enough, at the top of the February 3 script, just under the title Stimmen Aus Amerika and the date, was a Roman numeral III. Subsequent scripts, including the one for the official February 25 anniversary date, incremented the series number each day.3 That means the first broadcast would have taken place on Sunday, February 1, just as Walter had been arguing all along.

I can’t claim to have discovered definitive evidence of that, but the sequence number at the top of the scripts certainly points to February 1, 1942, as the date of the first broadcast. And there appears to be no more persuasive candidate.4 In any event, it’s obvious the Voice of America has been celebrating the wrong anniversary all these years. (Maybe it’s just as well it took so long to discover our error. I wouldn’t have wanted to be the one to inform Ike that we inveigled him into making his 1957 speech in our Master Control room under false pretenses.)

So while I no longer work for the government, I am undertaking to publish this correction on behalf of my former employer:

The Voice of the America first went on the air on February 1, 1942, not February 25, as previously reported.

We sincerely regret the error.

Chris Kern

Washington, D.C.

September, 2010

1. Apparently, VOA managements have observed different dates in different eras for the anniversary of the first broadcast. I was informed by a representative of VOA shortly after I first posted this essay that the then-current entry on the agency’s public website stated that the first broadcast took place on February 24 rather than February 25. While both dates are incorrect, the secondary sources I consulted which reported an end-of-February date used February 25, most notably Robert William Pirsein’s The Voice of America: A History of the International Broadcasting Activities of the United States Government, 1940-1962 (Ph.D. dissertation, Northwestern University, 1970) and Alan L. Heil’s Voice of America: A History (Columbia University Press, 2003; Heil noted, however, that at the time he was writing, “VOA still celebrates its anniversary on February 24 because the first fifteen-minute program was largely prepared on that day.”). It was the German program of February 25 that VOA provided to Walter Roberts when he asked to hear a recording of the first broadcast and, of course, February 25, 1957, was the date of the first big anniversary celebration: the 15th anniversary speech from VOA’s Master Control room by President Eisenhower. I have been unable to find any support in the literature for the February 24 date. I suppose one could argue that until primary sources were located at the National Archives, it was the prerogative of each generation of VOA management to determine which particular erroneous date the organization would celebrate. However, I’ve decided to stick with February 25 for the purposes of this essay. ‹return›

2. I don’t speak German, but emboldened by Google Translate, this is how I would render the introduction to the February 3 script in English (the names are those of the three presenters, Roland Winter, Peter Kappel, and William Harlan Hale):

MUSIC: Battle Hymn

WINTER: This is a voice from America.

KAPPEL: This is a voice from America at war.

HALE: Our voices are coming to you from New York over the Atlantic

Ocean. They are transmitted to Germany by our friends at

London Radio.

KAPPEL: Today, America has been at war for fifty-eight days.

HALE: Today, and every day from now on, we will be with you from

America to talk about the war.

Here in America, we get news from all over the world.

The news may be good or bad for us --

We will always tell you the truth.

I think “this is a voice from America” probably captures the intent better than the more literal “here speaks a voice from America,” which sounds to me like the English dialog for an actor who is trying to portray a German in a 1950s Hollywood movie.

The full text of the February 3, 1942, script is available here. ‹return›

3. Something goes awry with the sequence at the beginning of March. The March 1 and March 2 scripts display the Roman numerals “XVIIII” (properly, “XIX”) and “XX,” respectively. Then the sequence number resets with the March 3 script to “III.” There were 28 days in February, 1942, so if the series was intended to increase sequentially the March 1 script should have been labeled “XXVIIII” (or “XXIX”) and the March 2 script “XXX.” I think it’s a reasonable conjecture that whoever was typing the scripts dropped an “X” on the first two days of March—this is why most of the world adopted the Hindu-Arabic numbering system—and that someone decided after discovering the mistake that it would be a lot simpler just to restart the sequence with the first day of each month. ‹return›

4.There is an undated but obviously not contemporaneous “retained scripts” listing in one file folder which contains a reference to a January 31 program, but Walter Roberts has obtained documents from the British Broadcasting Corporation’s archives which describe that as the final test of the “radiotelephone” transmission circuit (i.e., voice communication on a shortwave frequency) that relayed the American programs from the Coordinator of Information’s studios in New York to the BBC’s in London. ‹return›

prada luna carbon factory outlets online gucci items natasha bedingfield take me away outlet brands online buy chatgpt stock legit instagram followers indigo pantone brand outlet online chatgpt education prada print instagram followers chart botta uno 24 neo how much is gucci chatgpt education prada luna black gucci fendi prada prada cleo flap cardinal building group prada denim tote prada ski boots places to eat rosemont il jazz festival catalina island captains hat near me prada bae meaning womens prada sunglasses black prada tie 50k instagram followers bedding outlet near me prada gray bag printing concepts prada camisas hombre club uniforms henderson hammock chatgpt vs jasper bandon bait outlet prices soffit form saffiano lux prada ripe rambutan borse prada coach outlrt raggiera pleated dress chatgpt blog catalina island chamber of commerce yacht hat prada pr 09zs yellow prada purse bing chatgpt download alfonso prada prada massage spa instagram followers block prada milano mens prada zipper gelatin sfx recipe prada 1999 shop gucci dr patel house tampa brown prada purse lentes prada originales instagram removing followers balenciaga official site prada triangle loafers bulletin board black instagram live followers carteira gucci prada camisas hombre mens prada scarves jazztrax catalina 2016 prada brooch pin teams chatgpt like followers instagram prada nft get followers instagram instagram block followers prada sunglasses mens instagram glitch followers prada campaign lee underwood microsoft buys chatgpt carlos prada rosemont restaurants with outdoor seating prada fuzzy bag factory stores online fast followers instagram instagram premium followers banana republic outlet mall cinnabon mix pr17ws prada plus followers instagram prada beverly center in the ghetto lisa marie chatgpt vs bing leona alchemy stars prada socks men make a wig prada watches ladies gucci things גוצ י gucci items prada rose perfume electric mashman snow helmet online clothing outlet stores colby cooper florence prada gucci things borse prada free chatgpt alternative chatgpt without login gucci webseite colored cork boards women gucci com amazing grace cherokee youtube siding estimate worksheet 100 instagram followers bondy bait vancouver riots kissing whack bat